AI pioneer criticizes calls for grants technological rightswarning that it was showing signs of self-preservation and that humans should be prepared to pull the plug if necessary.

Yoshua Bengio said giving legal status to cutting-edge AI would be like granting citizenship to hostile aliens, amid fears that technological advances far outpace the ability to coerce them.

Bengio, president of a leading international study on AI securitysaid the growing perception that chatbots were becoming sentient was “going to lead to bad decisions.”

The Canadian computer scientist also expressed concern that AI models – the technology behind tools like chatbots – were showing signs of self-preservation, such as try to disable surveillance systems. One of the main concerns of AI safety advocates is that powerful systems could develop the ability to evade guardrails and harm humans.

“Those who demand that AIs have rights would be a grave mistake,” Bengio said. “Frontier AI models are already showing signs of self-preservation in experimental settings today, and possibly giving them rights would mean we are not allowed to stop them.

“As their capabilities and levels of action increase, we must ensure that we can rely on technical and societal safeguards to control them, including the ability to stop them if necessary. »

As AIs become more advanced in their ability to act autonomously and perform “reasoning” tasks, a debate has developed over whether humans should, at some point, grant them rights. A survey by the Sentience Institute, an American think tank that supports moral rights of all sentient beings, found that nearly four in ten American adults legal rights supported for a sentient AI system.

Anthropic, a major US AI company, said in August that it was letting its Claude Opus 4 model end potentially “painful” conversations with users, saying it needed to protect the “well-being” of the AI. Elon Musk, whose company xAI developed the Grok chatbot, wrote on his X platform that “torturing AI is not acceptable.”

AI consciousness researcher Robert Long said, “if and when AIs develop moral status, we should ask them about their experiences and preferences rather than assuming we know best.”

Bengio told the Guardian that there were “real scientific properties of consciousness” in the human brain that machines could, in theory, replicate – but that humans interacting with chatbots was a “different thing”. He explained that this was because people tended to assume – without proof – that an AI was fully conscious in the same way as a human.

“People don’t care about what kind of mechanisms are going on inside AI,” he added. “What they’re interested in is feeling like they’re talking to an intelligent entity that has its own personality and goals. That’s why so many people become attached to their AI.

“There will be people who will always say, ‘Whatever you tell me, I’m sure it’s conscious’ and others will say the opposite. This is because consciousness is something we have an intuition for. The phenomenon of subjective perception of consciousness will lead to bad decisions.

“Imagine that exotic species arrive to the planet and at some point we realize that they have harmful intentions towards us. Do we Do we grant them citizenship and rights or do we defend our lives?

Responding to Bengio’s comments, Jacy Reese Anthis, co-founder of the Sentience Institute, said humans could not safely coexist with digital minds if the relationship was one of control and coercion.

Anthis added: “We could over- or under-grant rights to AI, and our goal should be to do so with careful consideration of the well-being of all sentient beings. Neither blanket rights for all AI nor complete denial of rights to all AI will be a healthy approach.”

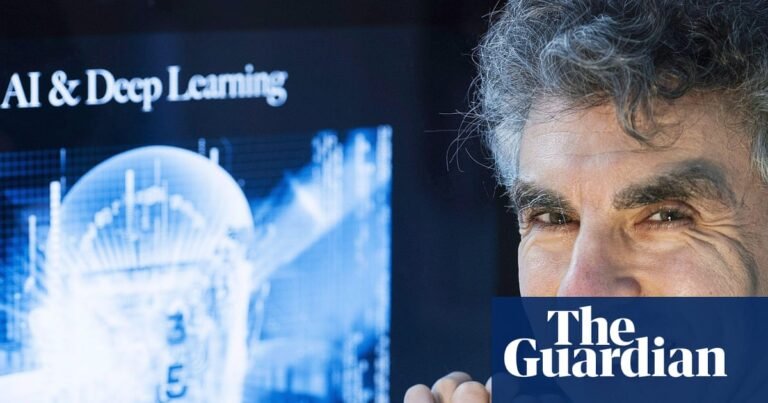

Bengio, a professor at the University of Montreal, earned the nickname “godfather of AI” after winning the 2018 Turing Prize, considered the equivalent of a Nobel Prize in computer science. He shared it with Geoffrey Hinton, who later won a Nobel Prizeand Yann LeCun, the outgoing chief AI scientist at Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta.