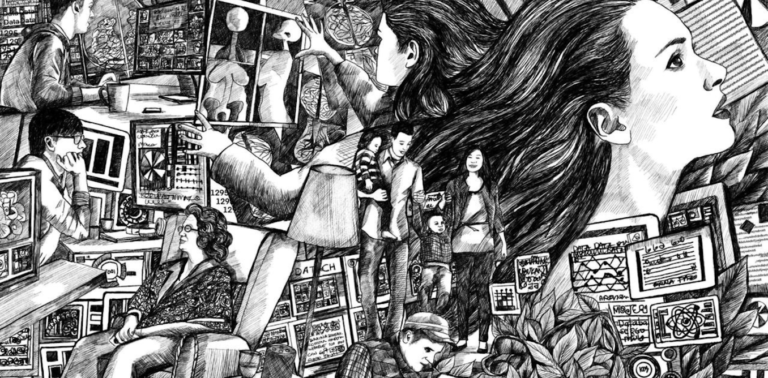

Artificial intelligence (AI) is not just made up of data, chips and code: it is also the product of the metaphors and stories we use to talk about it. THE how we represent this technology determines how the public imagination understands it and, by extension, how people conceive of it, use it, and its impact on society as a whole.

Which is worrying, numerous studies show that the predominant representations of AI – anthropomorphic “assistants”, artificial brains and the omnipresent humanoid robot – have little basis in reality. These images may appeal to businesses and journalists, but they are rooted in myths which distort the essence, capabilities and limitations of current AI models.

If we misrepresent AI, we will have difficulty truly understanding it. And if we don’t understand it, how can we hope to use it, regulate it, and operate it in a way that serves our common interests?

The myth of autonomous technology

Distorted depictions of AI are part of a common misconception that academics Langdon winner dubbed “autonomous technology” in 1977: the idea that machines have taken on a life of their own and independently act on society in an intentional and often destructive manner.

AI offers us the perfect embodiment of this, as the narratives surrounding it flirt with the myth of intelligent, autonomous creation – as well as the punishment for assuming this divine function. It’s an ancient trope, one that has given us stories ranging from the myth of Prometheus to Frankenstein, Terminator and Ex Machina

This myth is already evoked in the ambitious term “artificial intelligence”, invented by a computer scientist. John McCarthy in 1955. The label established itself despite – or perhaps because of – the various misunderstandings it provokes.

As Kate Crawford succinctly argues in her AI Atlas: “AI is neither artificial nor intelligent. Rather, artificial intelligence is both embodied and material, composed of natural resources, fuel, human labor, infrastructure, logistics, histories and classifications.”

Most of the problems with the dominant narrative of AI can be traced to this tendency to portray it as an independent, almost alien entity, as something unfathomable that exists outside of our control or decisions.

Misleading metaphors

The language used by many media outlets, institutions and even experts to discuss AI is deeply flawed. It is riddled with anthropomorphism and animism, pictures of robots and brains, have (always) fabricated stories about machines rebelling or acting in inexplicable ways, and debates about their supposed consciousness. All this is based on a dominant feeling of emergency, panic and fatality.

This vision culminates in the narrative that has driven the development of AI since its inception: the promise of artificial general intelligence (AGI), a putative human or superhuman intelligence that will change the world and even our species. Companies such as Microsoft And Open AI and technology leaders like Elon Musk predicted that AGI would be a a step always imminent for some time now.

However, the truth is that the path to this technology is unclear, and there is not even consensus on its feasibility.

Story, power and the AI bubble

This is not just a theoretical problem, as the deterministic and animistic vision of AI shapes a given future. The myth of autonomous technology inflates expectations of AI and distracts from the real challenges it poses, hindering a more informed and open public debate about the technology. A historical report of the AI Now Institute calls the AGI promise “the argument to end all arguments,” a way to avoid any questioning of the technology itself.

Along with a mix of exaggerated expectations and fears, these narratives are also responsible for inflating the AI economic bubble that various reports And technology leaders warn us. If the bubble exists and eventually bursts, we must remember that it was fueled not only by technical achievements, but also by a narrative that was as misleading as it was compelling.

Learn more:

Yes, there is an AI investment bubble – here are three scenarios for how it could end

Change the narrative

To repair the broken AI narrative, we must bring its cultural, social, and political dimensions to the fore. We need to abandon the myth of autonomous technology and start seeing AI as an interaction between technology and people.

In practice, this means shifting focus in several ways: from the technology to the humans who guide it; from a techno-utopian future to a present still under construction; from apocalyptic visions to real and present risks; from presenting AI as unique and inevitable to emphasizing autonomy, choice and diversity among people.

We can drive these changes in several ways. In my book, Technohumanism: a narrative and aesthetic design for artificial intelligenceI offer several stylistic recommendations to escape the autonomous AI narrative. These include avoiding using it as the subject of a sentence when it is in fact a tool, and linking AI to verbs that reflect what machines do (“process”, “calculate”, “calculate”, “predict”), rather than anthropomorphic verbs (“dream”, “imagine”, “create”, “mean”).

Playing with the term “AI” also helps us see how words can change our perception of technology. Try replacing it in a sentence with, say, “complex information processing,” one of the less ambitious but more precise names considered in its early days.

Important debates about AI, from those about regulation to its impact on education and employment, will continue to rest on shaky ground until we correct the way we talk about it. Crafting a narrative that highlights the sociotechnical reality of AI is an urgent ethical challenge. Successfully meeting this challenge will benefit both technology and society.

A weekly email in English featuring expertise from academics and researchers. It provides an introduction to the diversity of research emerging from the continent and examines some of the key issues facing European countries. Receive the newsletter!