Wildfire prevention has traditionally relied on blunt tools, such as rigid inspection cycles and emergency power shutoffs. Now, a new generation of tech startups is offering a more targeted approach: using artificial intelligence to help utility companies decide what to inspect – and where to intervene – before a spark turns into a fire.

The stakes are rising. In 2025, more than 77,000 wildfires were reported in the United States, significantly higher than the average over the past decade, and burned more than five million acres. For months, firefighting resources were strained. Droughts are recurring as the climate continues to warm, and wildfires now pose a threat almost year-round.

Factors ranging from weather and vegetation structure to power grid infrastructure and human activity make wildfires difficult to predict. Overstory, an Amsterdam-based company, has developed AI-based vegetation monitoring to help utility companies identify dangerous trees most likely to fall near power lines. The goal is to avoid sparks that could turn into a forest fire.

On supporting science journalism

If you enjoy this article, please consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribe. By purchasing a subscription, you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It’s a huge challenge. In California’s highest risk fire zones, contact with vegetation accounts for a significant portion of utility-caused fires. Combustible vegetation such as trees, grass or shrubs is the primary fuel for wildfires, and it’s one of the factors that utilities have control over, says Sonya Sachdeva, a cognitive scientist at Overstory, who focuses on wildfire decision-making.

To manage vegetation, utility companies typically send crews to walk power lines or fly helicopters periodically to collect information using lidar (light detection and ranging), a technology used to precisely map terrain with high-resolution three-dimensional images. But both methods can be slow, expensive and ineffective.

Overstory takes a different approach. To provide a focused map view, the company acquires high-resolution satellite imagery based on the locations of a utility company’s power grid. It then runs a set of proprietary computer vision models to identify tree height, encroachment, health and mortality, as well as factors relevant to wildfires, such as dead grass, shrubs and humidity levels.

The goal is not to replace people but to help utility companies know where to send their teams, says Fiona Spruill, CEO of Overstory. “We make our suggestions based on our analysis. But ultimately the decisions are made by the humans on the ground, standing in front of the trees,” she explains.

The results are promising. One of Overstory’s customers, Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E), saw a nearly 50% drop in the number of fires linked to vegetation as a presumed trigger in 2025 compared to the previous year, according to Andrew Abranches, PG&E vice president of wildfire mitigation.

But technology has limits. Overstory data provides frequent snapshots, but it is not a live feed; satellite imagery still lags behind real-time alerts from a network of cameras. “Any modeling project has a certain degree of uncertainty,” says Sachdeva. “But there’s always a human in the loop when we suggest something.”

Another technological front targeting fires, sometimes called firetech, is the push to develop AI-based detection tools. Pano AI, a San Francisco-based wildfire detection company, has designed its own pan, tilt, and zoom cameras that can scan 360 degrees to look for anomalies. Image sets are uploaded 24/7 to its cloud-based AI monitors to detect daytime smoke and nighttime heat signatures, which are supplemented by additional feeds such as geostationary satellite data and information from emergency services.

The AI models send alerts to command centers like PG&E’s Hazard Awareness Warning Center in San Ramon, Calif., where analysts check for threats before dispatching crews.

Jason Henry/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Experts cross-reference each AI detection with camera images to differentiate smoke from lookalikes such as fog, dust or clouds, explains Sonia Kastner, CEO of Pano AI. “Once a human verifies that it is indeed a fire, they send an alert via SMS and email,” she explains.

Pano AI’s partnership with Arizona Public Service (APS), Arizona’s largest utility company, has reduced fire response times over the past two years. “Pano (AI) routinely beat 911 calls,” says Scott Bordenkircher, APS forestry and fire mitigation director, and sometimes did so in “10 to 15 to 25 minutes,” allowing firefighters to respond sooner.

Bordenkircher notes, however, that the effectiveness of AI-based detection cameras also depends on a clear line of sight, meaning the smoke must rise high enough to be visible to the cameras. Detection is also limited to areas where cameras have been installed, leaving parts of Arizona without coverage.

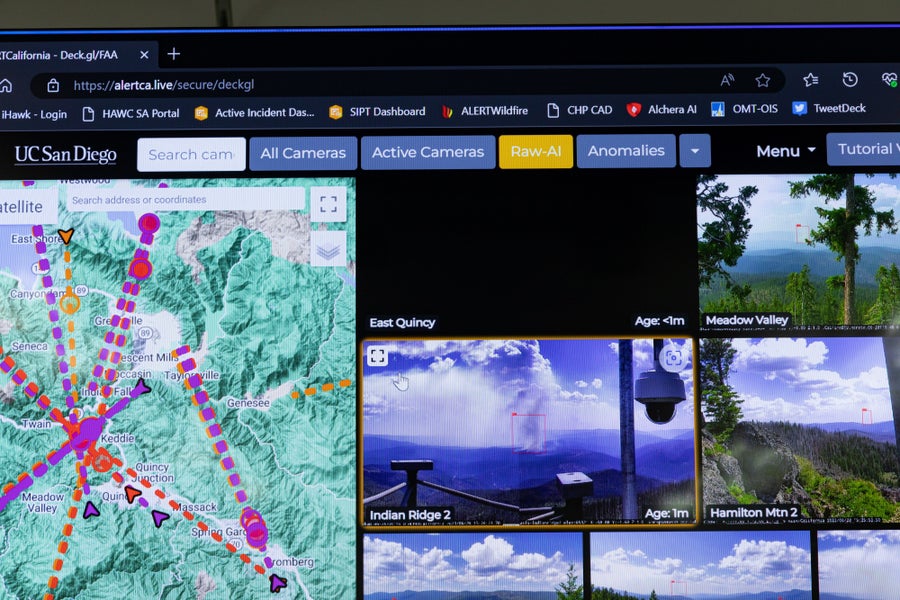

Pano AI was built on ideas that were first explored in academic wildfire research. One of these early efforts was ALERTCalifornia, a public safety program led by the University of California, San Diego, which uses cameras and AI to help local fire departments confirm wildfires in real time. Neal Driscoll, principal investigator of ALERTCalifornia, says that before the advent of AI, fire detection often started with calls to 911. “You have to send a battalion to check if the shots are real, and that takes a huge amount of time,” he says. But now, thanks to the detection system, fires can be identified and observed before 911 calls even arrive.

“We’ve dramatically reduced response time,” says Driscoll. The hope is that the time saved will translate into smaller fires.