In 1987, economist and Nobel Prize winner Robert Solow made a stark observation about the stagnant evolution of the information age: Following the advent of transistors, microprocessors, integrated circuits, and memory chips in the 1960s, economists and businesses expected that these new technologies would disrupt workplaces and lead to increased productivity. Instead, productivity growth has slowedgoing from 2.9% from 1948 to 1973 to 1.1% after 1973.

Newer computers were actually sometimes produce too much informationgenerating terribly detailed reports and printing them on reams of paper. What promised to be a productivity boom in the workplace proved for several years a failure. This unexpected result became known as the Solow productivity paradox, thanks to the economist’s observation of the phenomenon.

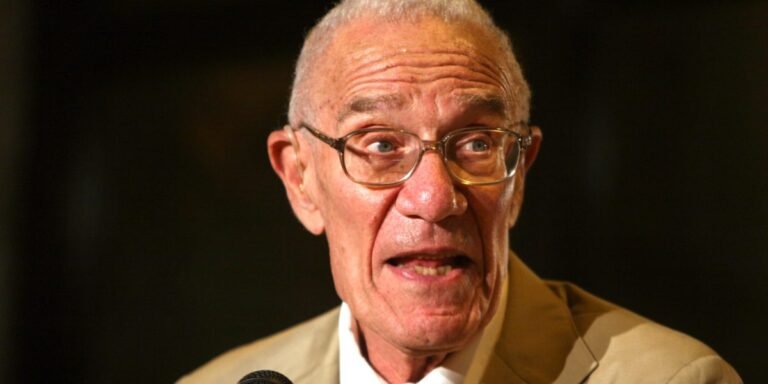

“The computer age is visible everywhere except in productivity statistics,” Solow writes in an article. New York Times Book Review article in 1987.

New data on how executives are or are not using AI shows that history is repeating itself, complicating similar promises made by economists and the founders of big tech companies about the technology’s impact on the workplace and the economy. Although 374 S&P 500 companies mentioned AI during their earnings calls (most of them said the company’s implementation of the technology was entirely positive), according to a report Financial Times analysis from September 2024 to 2025, these positive adoptions do not translate into broader productivity gains.

A study released this month by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that among the 6,000 CEOs, CFOs and other business leaders who responded to various business outlook surveys in the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany and Australia, the vast majority see little impact from AI on their operations. While about two-thirds of executives reported using AI, that usage only amounted to about 1.5 hours per week, and 25% of respondents said they don’t use AI at all in their workplace. Nearly 90% of companies said AI had no impact on employment or productivity over the past three years, the study noted.

However, business expectations for the economic and workplace impact of AI remain substantial: Executives also predict that AI will increase productivity by 1.4% and output by 0.8% over the next three years. While companies expected a reduction in employment of 0.7% over this period, the employees surveyed saw their employment increase by 0.5%.

Solow strikes back

In 2023, MIT researchers claimed that the implementation of AI could increase a worker’s performance by almost 40% compared to workers who did not use technology. But emerging data that fails to demonstrate promised productivity gains has led economists to question when – or if – AI will deliver a return on investment for businesses, which has ballooned to more than $250 billion in 2024.

“AI is everywhere except in incoming macroeconomic data,” Torsten Slok, Apollo’s chief economist, wrote in a statement. recent blog postinvoking Solow’s observation from almost 40 years ago. “Today, you don’t see AI in employment data, productivity data or inflation data.”

Slok added that outside of the Magnificent Seven, there is “no sign of AI in profit margins Or profit expectations.”

Slok cited a host of academic studies on AI and productivity, painting a conflicting picture of the technology’s usefulness. Last November, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis published in its Status of Generative AI Adoption report that it observed a 1.9% increase in cumulative excess productivity growth since the late 2022 introduction of ChatGPT. A MIT Study 2024however, found a more modest 0.5% increase in productivity over the following decade.

“I don’t think we should minimize 0.5% in 10 years. It’s better than zero,” study author and Nobel laureate Daron Acemoglu said at the time. “But it’s just disappointing compared to the promises made by people in the industry and tech journalism.”

Other emerging research may explain why: Workforce Solutions Company ManpowerGroup Global Talent Barometer 2026 found that among nearly 14,000 workers in 19 countries, regular worker use of AI increased by 13% in 2025, but confidence in the technology’s usefulness fell by 18%, indicating continued distrust.

Nickle LaMoreaux, IBM’s chief human resources officer, said last week that the tech giant would triple its number of young people hiredsuggesting that despite AI’s ability to automate some of the required tasks, displacing entry-level workers would create a shortage of middle managers down the line, endangering the company’s pipeline of leaders.

The Future of AI Productivity

Certainly, this productivity trend could be reversed. The computing boom of the 1970s and 1980s eventually gave way to a surge in productivity in the 1990s and early 2000s, including a 1.5% increase in productivity growth from 1995 to 2005 after decades of recession.

Economist and director of the Digital Economy Lab at Stanford University, Erik Brynjolfsson, noted in a Financial Times opinion article the trend maybe already reversing. He observed that fourth-quarter GDP was up 3.7%, although last week’s jobs report revised employment gains down to just 181,000, suggesting rising productivity. His own analysis pointed to a 2.7% rise in U.S. productivity last year, which he attributed to a shift from investing in AI to reaping the benefits of the technology. Former Pimco CEO and economist Mohamed El-Erian also highlighted employment growth and GDP growth continue to decouple in part due to the continued adoption of AI, a similar phenomenon that occurred in the 1990s with office automation.

Slok also viewed the future impact of AI as potentially resembling a “J-curve” of an initial slowdown in performance and results, followed by an exponential surge. He said whether productivity gains from AI would follow this model would depend on the value created by AI.

So far, the path of AI has already diverged from that of its computing predecessor. Slok noted that in the 1980s, a computer innovator had monopoly pricing power until competitors could create similar products. Today, however, AI tools are easily accessible due to “fierce competition” among large language models that is driving down prices.

Therefore, according to Slok, the future of AI productivity will depend on companies’ interest in leveraging the technology and continuing to integrate it into their workplaces. “In other words, from a macro perspective, value creation is not the product,” Slok said, “but how generative AI is used and implemented in different sectors of the economy.”